Guitar Tab for Every Time I Sing the Blues

It's pretty simple really: Whatever style of music you play if your rhythm stinks, you stink. And deserving or not, guitarists have a reputation for having less-than-perfect time.

But it's not as if perfect meter makes you a perfect rhythm player. There's something else. Something elusive. A swing, a feel, or a groove—you know it when you hear it, or feel it. Each player on this list has "it," regardless of genre, and if there's one lesson all of these players espouse it's never take rhythm for granted. Ever.

Deciding who made the list was not easy, however. In fact, at times it seemed downright impossible. What was eventually agreed upon was that the players included had to have a visceral impact on the music via their rhythm chops. Good riffs alone weren't enough. An artist's influence was also factored in, as many players on this list single-handedly changed the course of music with their guitar and a groove.

As this list proves, rhythm guitar encompasses a multitude of musical disciplines. There isn't one "right" way to play rhythm, but there is one truism: If it feels good, it is good. — Darrin Fox

Chuck Berry

Chuck Berry changed the rhythmic landscape of popular music forever. And his unique sense of groove and pocket is much deeper than it may seem upon first listen, as sideman extraordinaire and all around badass player Rick Vito pointed out in GP: "On many of his tunes, such as 'Carol,' 'Little Queenie,' and 'Johnny B. Goode,' you'll find Chuck playing a rhythm that is a cross between an eighth-note downstroke shuffle and a straight eighth-note rock feel. But he changed the accents of the shuffle so that it mixed those two feels and made the groove jump and swing more." In the end, the boundless energy and utter timelessness of Berry's music speaks for itself. As does the fact that without him there would be no Beatles, no Stones, and maybe no rock and roll. Hail! Hail! Rock and roll!

Lindsey Buckingham

"I want to make the big picture as interesting as possible," says Buckingham, who has merged pop songcraft and stellar guitar like few ever have. In fact, Buckingham strives for making everything he plays absolutely essential to the tune. His unbelievably inventive rhythm approach combines a wickedly precise right hand, propulsive fingerstyle figures that are informed by banjo rolls, and an attention to groove detail that can't be denied. His ability to make multiple, and different, rhythm guitar parts work seamlessly in a tune (like on all of Rumours), is as classy as classy gets. LB is an incredible stylist whose sense of time was honed on Chet Atkins and Merle Travis—i.e. never lazy.

Maybelle Carter

To call Carter's patented "Carter Scratch" rhythm guitar is selling it short—her style not only provided melody, harmony, and rhythm to the music of the Carter Family, it also laid the blueprint for all of country and folk music to come. "I love Mother Maybelle's playing," Marty Stuart told GP. "I thought she had the most beautiful touch I have ever heard." Equipped with her Gibson L-5, Carter would fill out the tunes by putting a melody on the bass strings with her thumb while alternating the chords on the treble strings with her index finger. Simple, yet beautifully effective.

Catfish Collins

As a member of the J.B.s, backing up James Brown, Collins' work is featured on the classics "Get Up (I Feel Like Being a) Sex Machine" and "Soul Power," among many others. Also dig the killin' instrumentals "The Grunt," and "These Are the J.B.s." Collins was with the Godfather of Soul for less than a year, eventually joining his brother Bootsy on Funkadelic's 1972 album America Eats Its Young. He eventually played on a slew of Parliament albums (that's Collins on the righteous funk anthem, "Flash Light.") too. Sadly, Collins passed away in 2010, but he left a hell of a funky legacy with his classic, greasy take on funk guitar.

Steve Cropper

"A lot of people have asked me why I didn't solo more," said Steve Cropper in 1994. "All I could ever say was that, when I solo, I miss my rhythm too much." Perhaps the ultimate team player, Cropper's rhythm method displays a funkiness that transcends simple sixteenth-note chord chanks or overtly syncopated figures. Instead, Cropper's weapon of choice is a sensei-like sense of when to strike with the perfect chord voicing, lick, or, well, nothing. "Otis Redding was a big influence on me," said Cropper. "He made me think and play a lot more simply, so that different notes would really count dynamically—find a hole and plant something in there that means something."

Bo Diddley

The only player on the list who actually has a rhythm named after him, Diddley— unlike a lot of guitarists—never worked as a sideman. "I always had my own group, he said. "I never played sideman for nobody." With some of the funkiest tones known to man, Diddley relied on his mutated rumba, often chucking chord changes altogether and putting all of his chips down on the groove. Classic sides such as "I'm a Man" and "Hey Bo Diddley" sound as fresh now as the day they were cut. Tell me now, who do you love?

Lonnie Donegan

Many players on this list were instigators of a revolution, but it would be tough to find an artist who was on the ground floor of a bigger uprising than Donegan, as he inspired an entire generation of British kids to pick up a guitar and pound away on three chords. Arguably rhythm guitar playing in its purest form, Donegan popularized skiffle—a hopped up mixture of swing jazz, blues, and folk with a driving acoustic guitar serving as the engine to make it go. It's not hard to imagine teenagers such as John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Pete Townshend completely losing their minds upon hearing Donegan's "Rock Island Line" for the very first time.

Cornell Dupree

"I'll push my groove button and groove," said the late, great Dupree, who passed away earlier this year. Dupree played with more people than he could even remember—from Streisand to Ringo and Midler to Miles—but he's most famous for his work with Aretha Franklin (Live at the Fillmore, and Amazing Grace are particularly savory), Donny Hathaway's Live, and Dupree's personal fave, King Curtis' Live at the Fillmore West. Dupree's signature rhythmic style was supple, exhibiting equal parts gritty funkiness and understated elegance. Dupree's ethos was "less is more." If you have something to say, say it, and if you don't, stay out of the way.

The Edge

Harmonic, rhythmic, and textural, The Edge is a triple threat of rhythm guitar goodness. On U2's earlier records, such as Boy and War, he blew minds with his chimey echoes and efficient chord voicings, which packed an Ali-sized punch when combined with his huge sense of pocket and clockwork right hand. As the years wore on, his playing still exhibited the same elements, but on an even grander scale with The Unforgettable Fire and The Joshua Tree. As the '90s dawned, The Edge began hammering out distorted slabs of aggro power chording and getting funkier. "Rock and roll started out as dance music, but somewhere along the way it lost its hips." He said to GP in 2000. "The emergence of hiphop and dance culture upped the ante in the rhythm department—and there's no going back. Listeners aren't going to accept lazy rhythms anymore."

Don Everly

When Keith Richards name checks you as having a profound influence on his rhythm style, well, you're pretty damn influential. The Everly Brothers' breathtaking harmonies soared over a bed of ingenious guitar playing that was based around Don's clever intros and driving rhythms. "I tried to make my guitar sound like a drum—a rock and roll instrument for rhythm and rhythm fills," he said. Another arrow in the Everly quiver was open tunings. "I couldn't figure out why Bo Diddley sounded the way he did," said Everly. "Chet Atkins told me he thought he may be in open tuning, and he was right. So I began using open tunings like G, and that made us sound like three guitars instead of two."

The Funk Brothers

Robert White, Eddie Willis, and Joe Messina were the main 6-string components of Motown's house band in the label's heyday from the late '50s to the early '70s. An incredible string of hits—"My Girl," "My Cherie Amour," "Ain't No Mountain High Enough," "Let's Get it On," to name but a few— weren't just the product of amazing songwriters, they were also due to the arrangements the three guitarists played, and the care they took in crafting their parts. The group would meticulously work out their voicings, dividing the neck up to avoid muddying the arrangements. "Everybody knew his given job," explains White. "Mine was rhythm, Eddie would play a bluesy fill, and Joe would usually read something or play backbeats." Says Willis, "Joe was 'king of the backbeats.' Pianist/ bandleader Earl Van Dyke swears that he never heard Messina miss a backbeat during his entire Motown career!"

João Gilberto

Gilberto is one of, if not the architect of bossa nova. Dig into any of the legendary guitarist/eccentric's titles, especially his seminal late-'50s and early-'60s recordings, and you'll find wonderfully understated rhythm playing that, even at its most subdued, undulates with a sexy, swaying groove. The tricky syncopations of Gilberto's vocal melodies and his fingerpicked rhythms are a marvel, as he makes it all sound so completely effortless.

Freddie Green

"If you pruned the tree of jazz, Freddie Green would be the only person left," says Jim Hall. "If you listen to one guitarist, study the way he plays rhythm with Count Basie." Green was a master of making the guitar sink in the rhythm section. His use of two- and three-note voicings exclusively let the harmonically dense horn arrangements speak, yet allowed Green to add to the already formidable swing with his trademark fourto- the-bar rhythmic pulse. Green also chose to play unamplified. "It blends better with the bass and piano," he told GP. Much of Green's classic Basie work was done with Epiphone Emperor, Stromberg Master 400, and Gretsch Eldorado models.

Jim Hall

Hall's playing has always rendered labels meaningless. His groundbreaking work with Bill Evans, Ella Fitzgerald, and Ben Webster shows his modern approach to harmony and sympathetic ear for playing in a group. "I learned from Jimmy Giuffre— who has a very compositional approach to performing jazz—that a group should be in an evolving state like a mobile, with each player acting and reacting as the music is taking shape." To find new chord voicings, Hall turned readers on to this pearl in '83: "Sometimes I'll take two voices and either take them through a tune like "Body and Soul," or play them against a pedal tone, like open A for instance. You can get some interesting things if you try to get the notes going in different directions."

Richie Havens

His impassioned performance at Woodstock alone would be enough to ensure Havens' place in the rhythm guitar Hall of Fame. And although the late guitarist had a very successful career since the day he opened the 1969 festival, Havens' performance there did give the world its first "peak" at a guy with a moving, all-in, passionate acoustic rhythm guitar style. "I play so hard that I used to go through a guitar every year-anda- half," he told GP. "To me, playing guitar is just part of getting the song across—it's not really about being a great guitar player. I don't even know what I'm doing. I'm filling in the spaces I have to in order to be able to sing a song the way I really feel it."

Jimi Hendrix

A school unto itself, Hendrix's rhythm playing in many ways feels like an even deeper ocean than his astounding soloing. From "The Wind Cries Mary" and "May This Be Love" from Are You Experienced to his beautiful rhythm work on "Little Wing, "Castles Made of Sand," and "Bold as Love" from Axis: Bold as Love, Hendrix rolled his Curtis Mayfield-inspired chordal movement and tasty flourishes into a style all his own. The culmination of that style comes on Electric Ladyland's title track, which finds Hendrix expounding even further on the sultry double- stop slides and bubbling trills that connect the spacey, at times ambiguous, but always beautiful chord sequence.

James Hetfield

Metallica is arguably the most influential band of the past 30 years, and Hetfield's sound is the hugest part of that band, which is really saying something. From the beginning with Kill Em' All, Hetfield's right-hand precision, speed, and power would set a standard that all aspiring metal rhythm guys would struggle to match. "Maybe it's the German in me," says Hetfield, "but I always want the rhythms to be precise. It's hard to escape. It's how I play." The other thing that Hetfield popularized was the way to get the maximum heaviness out of riffs. "Downpicking is the key!" he exclaims. "It's tighter sounding and a lot chunkier." Who are we to argue?

Chrissie Hynde

With a punk rock attack and a melodic songwriting streak a mile wide, Hynde not only provides the emotional heft behind her tunes, she relishes the role of rhythm guitarist as ringleader. "I'm not a great player, but I make sure I surround myself with great players who'll do their best work when they're with me," she explains. "I've got the vision, and all I can do is lead my band to glory. I'm the scrappy punk element," she continues. "Sometimes if the playing gets too good, it can lack a certain something. You could hand a guitar to 50 players and the guy who started playing three months ago might play 'Louie Louie' better than Eric Clapton!"

Tony Iommi

The architect of all things heavy, Iommi fired the shot heard 'round the world with one simple, evil, and impossibly slow riff— "Black Sabbath," from the band's earth-shaking eponymous debut. From there it was one classic after another ("War Pigs," "Iron Man," Sweet Leaf," "Sabbath Bloody Sabbath," etc.) on which Iommi continued to deliver on the promise he made on that first Sabbath record. But as the band evolved post-Ozzy, Iommi's rhythm playing and songwriting evolved as well. The lead off track from Heaven and Hell, "Neon Knights," served to put the world on notice that Iommi was much more than a sludgy doomsday riff machine—he was ready to put some speed behind his riffs. The title track to Mob Rules is also a killer, as is "The Sign of the Southern Cross," where Iommi's use of space makes his entry riffs extra punishing.

Danny Kortchmar

"It's much easier to play a screamer solo over a heavy groove than it is to make that groove," insists Kortchmar, who, aside from being an accomplished soloist, songwriter, and producer, was a rhythm specialist. Kootch found his way onto records by a who's-who of heavy hitters including James Taylor, Carole King, Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, Don Henley, and Bonnie Raitt. Back in 1983, Kortchmar wrote a story in GP, "In Defense of Rhythm Guitar." "A good rhythm guitarist will inspire people in the band to play better," he said. "We can't have a world full of guys playing screaming solos—there have to be guys who can play songs, who can play rhythm guitar." As a pro's pro, Kortchmar also dropped some science on how to get your feel together: "The interplay between people is what makes music, and that's something you can't practice at home. You have to get out in the world and do it."

Alex Lifeson

"I've tried to develop a style that combines broad arpeggios and suspended chords," explained Lifeson. "They've been my two main target areas. Suspensions have been my trick for many years to make a trio sound big." Not very often are you treated to a body of rhythm work like Lifeson's, from classic riff rock ("Working Man") through heavy prog ("Xanadu") onto the textural '80s and '90s, deftly riding the heavier sonic zeitgeist all the way to 2011. Along the way, Lifeson has also incorporated more feels into his vernacular as well, including reggae (Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures) and funk (Roll the Bones). Lifeson has done it all, and never at the expense of his own personal voice.

Tony Maiden

During their heyday in the '70s, Rufus ruled the funk roost. And although lead vocalist Chaka Khan got most of the cheese, Maiden was in the engine room corralling jazzy changes into seemingly simple funky guitar parts that outlined the tunes perfectly, without ever taking your ear away from the vocal. In fact, Maiden enhanced everything around him. His playing throughout the classic "Sweet Thing" is dead sexy from the start, with an intro that is a textbook example of sultry sophisti-funk guitar.

Bob Marley

Music doesn't get much more rhythmic than Marley's, and any guitarist with a genuine interest in adding the reggae flavor to their palette would be well served to study what Marley and his cohorts Peter Tosh, Junior Marvin, and Early "Chinna" Smith committed to wax. Always restrained, never stiff sounding, and every upbeat skank the perfect note length (a skill really worth honing for all styles of rhythm guitar), Marley's oeuvre is a lesson in rhythmic meditation.

Johnny Marr

Is there a guitarist more influential in Brit pop? Marr's work with the Smiths showed the way for countless pop guitarists in the '80s, '90s, and beyond as he wrangled jangle and extended clean-toned arpeggios with a steadily grooving right-hand that would be equally at home in a dance band. Marr is also a master of using multiple guitars to create one big propulsive behemoth, with every part, lick, and chime accounted for. "I've always believed that any instrumentalist is basically just an accompanist to the singer and the words," he said. "That's borne out of being a fan of records before I was a fan of guitar players—I'm interested in melody, lyrics, and the overall song. I don't like to waste notes, not even one."

Curtis Mayfield

Mayfield is one of a handful of players on this list who basically invented a style. His ultra-lyrical comping connects chord changes in wonderfully inventive ways, with slippery double-stops and octaves and fleeting hammer-ons, while never overshadowing the bigger musical message. "Because I play with my fingers and play a chord along with the melody, my style suggests two guitars and the little melodic movements are just part of it," Mayfield told GP. Mayfield, who played exclusively in open F# tuning, was also a master of sublime wah, using it to accentuate parts and add textures.

Al McKay

One of the most visible purveyors of Jimmy Nolen-style funk guitar, McKay bolstered Earth, Wind & Fire's sound throughout the '70s on hits such as "Shining Star," "Sing a Song," and "Saturday Night." The lefty sports an uncanny knack for seamlessly intertwining funky, palm-muted single-note lines and finger-tight chordal work (the intro to "September," being one example which was cut with a Telecaster sporting a neckposition humbucker), all the while navigating the tune's changes and staying out of the way of the dense horn, string, and vocal arrangements.

Tom Morello

"When it comes to riffage, I'm all about the 1st and 3rd fingers and the 3rd and 5th frets—the same two strings on the same dots." That's how Morello describes his slabs of powerful pentatonic plundering on all of Rage Against the Machine's classic sides. Morello's mojo lies in the fact that he doesn't use a ton of distortion, and he doesn't tune down to silly extremes. His means to an end is a relentless dedication to the downbeat— the one. "In all the music that's richly satisfying to me," says Morello, "the ones are huge and unrelenting. It's not really a rule, but you'd be a fool to stray from it. It's good enough for James Brown!"

Leo Nocentelli

Aside from Jimmy Nolen, arguably no guitarist has had as big effect on funk guitar as Nocentelli. A master of staccato, single-note funk, and stinging, brash chords, Nocentelli deftly bobs and weaves in and around the Meters' impossibly funky grooves. It's no wonder the likes of Jimmy Page, Paul McCartney, and the Rolling Stones (who had the Meters open up for them on their 1975 tour) were huge fans of New Orleans' funkiest export. Armed with a Fender Starcaster (although he did cut the group's most popular tune, "Cissy Strut," with a Gibson ES-175), Nocentelli has a funky sixth sense for knowing when to tightly double a bass line or when to latch onto (or dance around) the drummer's syncopated hi-hat pattern. Aside from the Meters' classic tracks, Nocentelli and the Meters can also be heard on Patti LaBelle's "Lady Marmalade" and Robert Palmer's Sneakin' Sally Through the Alley.

Jimmy Nolen

The Godfather of funk guitar. Beginning with a single sixteenth-note break on James Brown's "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag," Nolen defined the funk guitar style, both rhythmically and harmonically, with simple two- and three-note chord voicings. "I started developing that when I played with Johnny Otis back in the '50s," said Nolen, who used a Gibson ES-175 and a Gibson Switchmaster on his first recordings with Brown, before moving to a Les Paul Recording and a Japanese- made Fresher Straighter Strat copy. "See, we used to play with so many different drummers—some were good but some were lazy. So I used to just try and play and keep my rhythm going as much like a drum as I could." For more of Nolen's pioneering style, dig "Cold Sweat," "There Was a Time," "Give It Up or Turn It Loose," and "Say It Loud—I'm Black and I'm Proud." Thanks Jimmy!

Jimmy Page

As much as he is remembered for being a heavy riff architect, much of Page's rhythmic identity is based in '50s rock and roll from influences such as Scotty Moore, James Burton, and Cliff Gallup. He also rolled a major wild card into his style, the whirling feel of Les Paul. When you throw all of that in with a hefty acoustic jones stoned on British Isles folk, an uncanny ear for modal tunings, and a good dose of riff thuggery (Johnny Ramone worshipped Page's "Communication Breakdown" assault), you end up with one of the electric guitar's most defining voices.

Joe Pass

An amazing solo guitarist and accompanist, Pass exhibited musical sophistication and sensitivity that are yet to be paralleled, including connecting the melodic dots with remarkable voice leading and walking bass lines. Pass's four duet albums with Ella Fitzgerald are must haves (Take Love Easy, Fitzgerald and Pass…Again, Speak Love, and Easy Living), as are his series of Virtuoso recordings. "The best way to get the jazz feel," says Pass, "is to play along with records or a group. It's something you have to learn to inherently feel."

Les Paul

Danny Gatton is one of the few guitarists that actually tried to cop Paul's chops, and Jeff Beck recently did a full-scale tribute to the Great Man at the Iridium in New York City—but nearly every guitarist from George Barnes to Jimmy Page acknowledges a debt of some sort to Paul. His mastery of jazz harmony and dizzying melody lines notwithstanding, Paul's echo-enhanced, Djangoinfluenced rhythmic foundations on unstoppable pop juggernauts such as "How High the Moon" and "Tiger Rag" shaped the course of commercial music for nearly a decade, and provided the template for slapback styles from rockabilly to country to surf and beyond.

Joe Perry

Although Perry's classic work with Aerosmith operated squarely in the blues/rock vein, he never sounded clichéd or staid. With healthy dollops of Jimmy Page's single-note funkiness, as well as some dirty Keith Richards chordal attitude, Perry rolled his influences into an inventive, grooving style that transcends simple classification. Perry's willingness to mix in filthy tones only enhanced his funk factor ("Get It Up" from Draw the Line is just nasty), and his use of 6-string bass on "Back in the Saddle" and "Draw the Line" showed that he was always willing to think outside the blues box. "Your sense of groove has a lot to do with the guys you're playing with," Perry told GP. "If they're really holding it down, you can float on top of it and drive the groove."

Prince

"A lot of cats don't work on their rhythm enough," said Prince to GP in 2004. "And if you don't have rhythm, you might as well take up needlepoint or something." One listen to any of Prince's tracks, from 1979's Prince to his most current, 20Ten, and it's clear that the dude's knitting skills probably suck. "I'm always trying to work the bass notes when I'm playing funk rhythms," he says, "the same way Freddie Stone from Sly and the Family Stone used to do it." Prince's rhythm style may be based on classic funk conventions, but his clever juxtaposition of tones and effects, as well as his undeniable rock rhythm chops, are a big reason why he's such a heavy hitter.

Johnny Ramone

"I always wanted the guitar to sound like energy coming out of the amplifier," said Ramone in '85. "Not even like music or chords. I just wanted that energy." Mission accomplished, Johnny. With his Mosrite plugged into a Marshall stack and a sledgehammer right-hand attack, Ramone wrote the book on punk guitar. "I was influenced by the New York Dolls, T. Rex, and Slade, but I can't play any of their songs," he said. "I can only play Ramones songs and the few covers that we do. I just like to play punk rock, and that's it—real loud rock and roll— no slow songs or soft songs."

Jerry Reed

Being a hotshot session guy and an accomplished songwriter doesn't hurt when it comes to having an evolved rhythm style. Reed's rhythm guitar approach encompassed Atkins and stanky backwoods funk—the intro to "Guitar Man" being an excellent example of the former, and "Amos Moses" a superb specimen of the latter. His playing on "Good Night, Irene" (from '73's Hot A' Mighty) is a textbook example of a rhythm performance that acts as a solo, an accompaniment, and a hook as he flaunts hybrid picking chops mixed with hip chord grips and bends that would be comical if they weren't so killer.

Django Reinhardt

If you can tear your ear away from his dazzling soloing long enough, you realize that Reinhardt's rhythm chops are just as impressive. Scary. His relentless swing utilizes the ultra-percussive "la pompe" strumming technique which makes the drummerless ensemble swing with a steamroller intensity, pushing the soloist to greater improvisational heights. Pull out your metronome, get a chart for "Minor Swing," and get crackin'. Then, work your way up to the much quicker "Limehouse Blues." You may not aspire to play Gypsy jazz, but working on these tunes is a blast and a guaranteed groove enhancer.

Tony Rice

Long ago, Rice was considered the heir apparent to his late mentor, Clarence White. It didn't take long, however, for Rice to forge his own identity, due in large part to the fact that he started to bring very nontraditional harmony to bluegrass music. Counting George Benson, Wes Montgomery, and Joni Mitchell as influences, Rice's concept of time (he credits Dave Brubek's "Take Five" for turning him onto odd time signatures) and colorful chord palette (he often cites Jerry Reed as having an influence on some of his dense, close-interval chords), coupled with his uncanny variations on simple rhythm patterns, have made him the bluegrass guitarist for a generation.

Keith Richards

Rock and roll's high priest of groove, Richards' lifetime of work with the Rolling Stones stands as a sonic monument to the hip-shaking power of rhythm guitar. His use of open-G tuning on nearly everything he's done since the late '60s spawned a style and sound that is still being imitated. "With open tunings, you can get a drone going so you have the effect of two chords playing against each other," he told GP. "It's a big sound." Richards' other contribution to the rock rhythm lexicon is the way he views the interplay between two guitars. "Rather than going for the separation of guitars, we try to get them to start to sound at a point where it doesn't matter which guitar is doing what," he explains. "They leap and weave through each other, so it becomes unimportant whether you're listening to the rhythm or the lead because in actual effect, as a guitarist, you're in the other player's head, and he's in yours."

Nile Rodgers

"I really developed my style while playing jazz standards like 'So What' with my guitar teacher in a club," says Rodgers. "He was comping in the traditional way, and I thought, 'What am I going to do? He's got it covered.' So I tried to fill in the holes, swinging it like a drummer, and the whole club went 'Whew! That is funky!'" The rest is history as Rodgers went on to cut some of the most groovin' guitar playing known to man with Chic. His signature funkiness on "Le Freak" and "Good Times" have frustrated many a weekend warrior, as the riffs seem so simple, but getting them to sound and feel as good as Rodgers does, well, that's the trick now, isn't it?

Rudolf Schenker

"When something is in the pocket, it drives me," says Schenker. "It gives me an outstanding power, like I'm surfing on a wave. When the groove isn't right, I feel lost a little bit. It's very hard work and it's somehow not fun anymore." Suffice to say, the groove is important to Schenker, who—aside from possessing one of the best combinations of savage tone and feel in the history of metal— has written some of the most timeless riffs as well. "I don't care about the technical stuff," he says. "What's important to me is the attitude, the drive, and the feeling."

Earl Slick/Carlos Alomar

"David Bowie's Station to Station was the first time Carlos and I really zeroed in on how we should play together," says Slick. "We mixed my rock thing in with Carlos' funk thing and I think we came up with a pretty unique guitar combination—two guys who don't play anything alike making it work." Indeed. Slick and Alomar provided Bowie some legitimate funk and attitude during his Thin White Duke phase, creating chattering rhythmic figures (Alomar) and snarling chord bursts (Slick). Dig "Golden Years" and "Stay" from Station to Station for proof, and if that doesn't convince you, listen to "Fame" from Young Americans. Oh my.

Steve Stevens

"I think of songs as environments, or little movies," said Stevens in 1989. "And that usually dictates the sound I go for and the playing approach I take." With Billy Idol in the '80s, Stevens packed a cornucopia of rhythmic goodness into three-minute pop tunes better than anyone. His use of textures, noise, and good old-fashioned groove proved to be an unbeatable combination. "My playing reflects more of the English R&B sound," says Stevens, distancing himself from '80s texturalists such as Andy Summers and The Edge. "We're similar to an extent, but I do it in Day-Glo! I play with a much more distorted sound." As for his killer time and ability to hit the right chord at exactly the right time, Stevens says it's simple: "Have a singer who will beat the piss out of you if you don't stay in the pocket—that's how I learned. Billy Idol made me realize that technique is there as a secret weapon. If the guitar is full-on all the time, that's pretty damn boring."

Andy Summers

Sonically, Summers is possibly the most influential player on this list. His frothy chorus and dubapproved delays became irreplaceable cogs in the Police's machine. But dig deeper and you find Summers' grasp of reggae feels, as well as his propensity to extend chords (giving even the simplest progression, a modern makeover), were also a huge part of his sound. "I used to be in bands with keyboard players where we had to always watch out for what the other guy was doing harmonically, because there would be conflict," he explains. "I didn't have that restriction in the Police, so I could stretch chords out and make my rhythm parts more orchestral."

Pete Townshend

To call Townshend's rhythmic contributions to rock guitar "huge" doesn't even begin to describe the influence he has had. Yet, it's not as if he inspired a legion of Townshend sound-alikes. His style—which boasts an incredible right-hand strumming technique— has remained intensely singular and attached to the tunes that embody it. Townshend possess the ninja-like skill of knowing when one big chord will not only do the job, it's big enough to be the hook (see "Won't Get Fooled Again"). Those are some onions, my friend. More than anyone, Townshend has also shown how high an art form rhythm guitar can become in a rock and roll band.

Eddie Van Halen

Although his solos were fodder for nearly every guitarist growing up in the late '70s/ early '80s, Van Halen's rhythm work never got quite as much attention, which is a damn shame because there's gold in them there riffs! You had your vicious metal chuggers ("Romeo Delight," Light Up the Sky," "D.O.A."), some pretty stuff (the woefully underrated "Secrets"), and the weird ("Sinners Swing," "House of Pain"). VH's rhythm work was oftentimes just as gonzo as his solos, frequently exhibiting the same careening racecar vibe, and he didn't necessarily come from a certain "school" of rhythm guitar. Like his soloing, his rhythm playing was intensely personal (for my money, the intro to "5150" is a textbook example of this) and seemingly easy to grasp on the surface, but once you dive in, you find there's a lot to digest.

Jimmie Vaughan

Although he could certainly solo with the best of the blues cats, Vaughan's calling card in the shred-heavy '80s was as a blues rhythm specialist. "When I started out playing guitar, all I wanted to do was play that Jimmy Reed groove—it just feels real good," Vaughan told GP. "Then I made it my business to figure out the guitar interplay between Reed and his co-guitarist Eddie Taylor. I tell you what, it sounds real easy when you first hear it, but listen closely. The way they lock and form that deep groove is not easy. It's a whole other thing." The same could be said for Vaughan's rhythm work, as he makes it seem so easy—the sign of a true master.

Alex Weir

As part of the Brothers Johnson and Talking Heads, Weir was the ultimate funky ringer. This was especially true in Talking Heads, as evidenced by the epic concert film, Stop Making Sense. Working over a Music Man Sabre, Weir's contributions to the Heads' collective funk cannot be underestimated. "This Must Be the Place (Naïve Melody)" and his impossibly dope comping on "Burning Down the House" are as infectious as they are musical, and his guitar interplay with David Byrne on "Big Business/I Zimbra" is a clinic in relentless sixteenthnote funk. Damn!

The Wrecking Crew

This loose-knit collective of musicians played on a plethora of '60s and early-'70s hits by everyone from the Carpenters to the Beach Boys to Simon & Garfunkel to the Monkees—the list goes on and on. And everybody knows you don't get huge, timeless hits with lousy rhythm guitar work, right? The roster of guitarists in the Wrecking Crew goes from giants of jazz such as Barney Kessel and Howard Roberts to studio rats Tommy Tedesco and Carol Kaye to arranger/guitarists such as Al Casey and Billy Strange—all master sight-readers with impeccable feel. Cats such as Glen Campbell, Louie Shelton, Jerry Cole, and Mike Deasy (among others) could be counted on to deliver the snazzy new rock and roll rhythms of the day—noise that guys like Kessel and Tedesco hated—but they loved the paychecks!

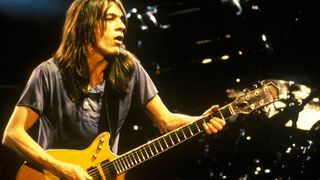

Malcolm Young

Has anyone personified the role of a rhythm guitarist in a rock band better than Malcolm Young? No, they haven't. For over 35 years in AC/DC, not only did he play some of the most swaggering, swinging, balls-to-the-wall rock and roll guitar ever, he did it with zero solos. Young knew exactly what his role was as a rhythm guitarist in a rock and roll band, and he thrived in it. "Learning an instrument has to be natural," he says. "If you stop to think about playing, the feeling just goes." Feel was always behind what Young did. Without it, he would be just a dude strumming chords. "It probably has something to do with the attitude I put into it. I don't think what I do is hard, really. If it doesn't swing, it doesn't mean a thing. That's about it."

Source: https://www.guitarplayer.com/players/the-50-greatest-rhythm-guitarists-of-all-time

0 Response to "Guitar Tab for Every Time I Sing the Blues"

Publicar un comentario